What barriers do men face in help-seeking when they have experienced abuse?

By Liz Bates, Julie Taylor, Attilio Colosi and Andrew Creer

We understand from research working with women who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) that there are multiple barriers to their help-seeking and leaving an abusive relationship. The societal narrative around IPV has often focused on asking why people (but specifically women) don’t “just leave” their abusive relationship. It has led many campaigners and women’s organisations to challenge this narrative and change the question from “why doesn’t she just leave?” to “why doesn’t he stop?”, asserting that the former lays blame for the cessation of the abuse at the hands of the victim.

Whilst the motive behind the challenge is to ensure that victims are not being blamed for their victimisation, it is important that we still understand the barriers that victims face in leaving, reporting, and help-seeking. It is only through this understanding that we can put resources or plans in place to facilitate this.

Much of what we have understood about barriers to help-seeking has come from working with women, as historically much of the literature exploring IPV has focused on men as perpetrators and women as victims with a very gendered focus. However, research across this area has now demonstrated that IPV victims occur across the gender and sexuality spectrums which calls for a need to understand any specific barriers that might exist for these groups.

Barriers to men’s help-seeking

Within the academic literature there is now a developing body of literature that explores men’s experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV). We know that men experience physical, sexual and psychological/emotional abuse, and that these experiences can significantly impact their physical and mental health, and often their relationships with their children.

In a new study, we utilised an anonymous online survey to ask men about the barriers they have experienced in help-seeking for abusive experiences. We utilised this method to facilitate and encourage disclosure; ManKind Initiative, a UK male victim’s charity, noted how important anonymity is with men calling their helpline and that a significant number would not have called if they had had to give any personal details. Below, we briefly detail two barriers that we found within our analysis of the data.

Personal barriers

When men were asked about the personal barriers that they faced when it comes to seeking help, we found that the main barriers were feelings of shame and embarrassment as a result of their situation. This was clearly demonstrated by some of the responses:

“ashamed and embarrassed”

“Very much feeling both ashamed and embarrassed”

These feelings of shame and being embarrassed seemed to be a result of perceptions around normative expectations of IPV and gender. One participant describes being hospitalised and seeing four posters about domestic violence, all of which:

“…were from the female perspective”

There is a clear perception and expectation about IPV being gendered; this can also be seen in the fact the domestic abuse policy falls under the Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy; a strategy where there is no equivalent for men and boys, furthering the view that IPV is gendered. Another participant describes credibility as being a barrier to help seeking as:

“people… simply don’t recognize this kind of abuse.”

These feelings of shame and embarrassment described by the men here supports the existing literature that shows men hold less favourable attitudes towards help seeking and that these attitudes are as a result of men wanting to adhere to masculine gender normative roles and behaviour. Research suggests that male socialisation through things such as sport or male dominated careers (e.g., the army) can implement an indoctrination of masculine expectations which in turn contributes to the construction of male gender identity and behaviour expectations. This acts as a personal barrier because men, as a group, are assumed to have power, and there is a stigma attached to men who do not meet these societal expectations. This can be embarrassing and cause negative attitudes towards help seeking and a reluctance to access it. This may be illustrated by the response from a participant who describes himself as a “6 foot 2 ex squaddie” saying:

“…Moaning about my wife beating me up could turn a friend who admired me into someone who either viewed me as a failure or suspicious that I was really to blame within minutes.”

We found several other personal barriers that stopped men seeking help. For example, trying to keep the family together, false allegations and failure of police and other support organisations to intervene. However, these all in some way or another link to feeling embarrassed, ashamed, or both, as a result of self-stigmatisation from comparing themselves and their situation to what society expects.

Experiences of Control

The men who participated in the study identified a range of methods that were used to control them and how this impacted on their help-seeking. Although we primarily discuss these two themes in isolation, they are closely intertwined; experiences of control may inform a victim’s self-beliefs, and ultimately whether they disclose the abuse and/or seek help. There were recurrent types of control, for example false allegations were threatened or carried out to control the victim, below are quotes extracted from the data:

“I know with certainty that I would have false allegations levelled at me, and this is a major reason why you stay”

Some victims resorted to methods to attempt to challenge any future attempt of false allegation:

“I was threatened with two false allegations (Alcoholism and Threatening with a Knife), I used a digital voice recorder after that and kept diaries. I still keep a diary of events now”

These examples highlight the way false allegations can be used as method of control and why some men remain in a relationship with their abusive partner. The types of false allegations varied from rape/sexual assault to physical violence, this method of control was often more than the threat of police reporting, but seen as a specific area targeted to control them through fear of losing access to their children.

“False allegations were made in order to obstruct contact and access to my child”

Criminality may inflate the perceived risk by services as to whether they will allow parental access, and is also considered in family court proceedings. The use of these tactics to control the men produces a significant barrier to seeking help. Throughout the data it is often stated that there was a fear of not being believed by authorities, which increases the power these methods of control hold against male victims of IPV. Furthermore, if custody of the child was primarily organised in favour of the mother, men spoke of the manipulation of the children to affect their parental relationship (parental alienation). This was used to emotionally abuse (and control) the victim after a separation by continuing the narrative that the victim was to blame for the circumstances which had occurred, which links in with the personal barriers discussed previously. The methods of control discussed are a snapshot of some prolific means women utilised to control their partner, how these impacted them, and ultimately reasons why male victims of IPV may not disclose or seek help.

Taylor, Bates, Colosi and Creer (2019)

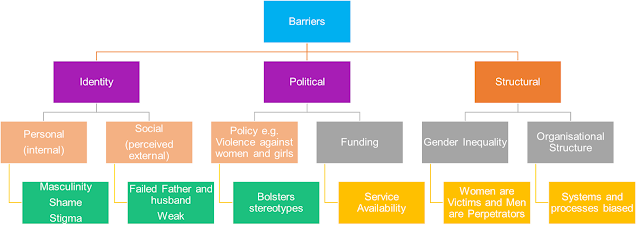

Our analysis of this large data set has revealed the myriad of factors that can affect men’s recognition of their need for help and their efficacy in seeking that help. Figure 1 (below) is a thematic map of our analysis and highlights the complexity of barriers that men experience:

Figure 1: Thematic map of barriers to help-seeking

In our upcoming paper, we discuss these barriers in more detail with a specific focus on those related to personal and social identity. We hope our findings can be useful to both academics and practitioners in helping them understand the number of obstacles men face. We further hope, more importantly, that by discussing these barriers beyond academia we may be able to challenge the wider narrative that exists around men’s help-seeking, and could encourage more services and agencies to make changes to reduce some of the political and structural barriers. We hope that men who engage with this work may feel they are not alone and that their experiences and difficulties in disclosing are shared by many others; this may in at least a small way facilitate a reduction in these personal or identity barriers for those men.

The research team:

The research team for this project is made up of both staff and voluntary research assistants at the University of Cumbria. The Student Research Assistant Volunteer Scheme runs within the Psychology department at the University, it allows students at all levels the opportunity to get involved with staff research projects. It gives students the opportunity to develop their research skills, gain experience for their employability, and develop confidence in working in research and within research teams.

Attilio has just graduated with a first class degree in Applied Psychology. Attilio said “The research assistant scheme has been instrumental in enhancing my research skills and knowledge by working with ‘real world’ data, and writing academically with the exciting prospect of being named on a published academic article. The scheme has increased my confidence in research projects outside University (specifically within the NHS) to contribute more to these than I would have previously to working on the scheme.”

Andy is a third year student on our Psychology degree. Andy said “I found taking part in the research assistant volunteer scheme to be rewarding and valuable experience which has helped me to further and implement skills that I have learnt in lectures in a real and current research project. The scheme has been very beneficial for my degree and future prospects in the area of psychology, especially because I’ll be included in the publication of the paper meaning my contribution has made it into the current academic literature.”

Importantly, working in these research teams are mutually beneficial for staff and students. I have worked within this research area for 12 years and spend a lot of my research time involved within the literature and talking to other academics who share the interest. I enjoyed working with Attilio and Andy and found them to be a great asset to the research team. Their insight and ideas into both the literature and the data brought a different and important perspective; their “fresh eyes” meant exploring aspects of these men’s experiences that I had not previously considered.

This project was jointly led by Liz and Julie, and working with Attilio and Andy. Julie is the principal lecturer responsible for the psychology and psychological therapies provision within the Institute of Health. Julie works closely with colleagues (student and staff) on a number of projects pertaining to social justice and inclusivity.

If anyone has felt upset or distressed by anything they have read here, please note there is support available through these agencies:

Women’s Aid – Domestic Violence Service providing a wide range of services to women experiencing domestic abuse.

0808 2000 247

Mankind Emotional support and practical advice for men experiencing domestic violence.

01823 334244

Galop – Support and advice for people in the LGBTQ+ community who are experiencing domestic violence

0800 999 5428

If anyone would like to find out more about the Student Research Assistant Volunteer Scheme then please email Liz on Elizabeth.Bates@cumbria.ac.uk

We understand from research working with women who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) that there are multiple barriers to their help-seeking and leaving an abusive relationship. The societal narrative around IPV has often focused on asking why people (but specifically women) don’t “just leave” their abusive relationship. It has led many campaigners and women’s organisations to challenge this narrative and change the question from “why doesn’t she just leave?” to “why doesn’t he stop?”, asserting that the former lays blame for the cessation of the abuse at the hands of the victim.

Whilst the motive behind the challenge is to ensure that victims are not being blamed for their victimisation, it is important that we still understand the barriers that victims face in leaving, reporting, and help-seeking. It is only through this understanding that we can put resources or plans in place to facilitate this.

Much of what we have understood about barriers to help-seeking has come from working with women, as historically much of the literature exploring IPV has focused on men as perpetrators and women as victims with a very gendered focus. However, research across this area has now demonstrated that IPV victims occur across the gender and sexuality spectrums which calls for a need to understand any specific barriers that might exist for these groups.

Barriers to men’s help-seeking

Within the academic literature there is now a developing body of literature that explores men’s experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV). We know that men experience physical, sexual and psychological/emotional abuse, and that these experiences can significantly impact their physical and mental health, and often their relationships with their children.

In a new study, we utilised an anonymous online survey to ask men about the barriers they have experienced in help-seeking for abusive experiences. We utilised this method to facilitate and encourage disclosure; ManKind Initiative, a UK male victim’s charity, noted how important anonymity is with men calling their helpline and that a significant number would not have called if they had had to give any personal details. Below, we briefly detail two barriers that we found within our analysis of the data.

Personal barriers

When men were asked about the personal barriers that they faced when it comes to seeking help, we found that the main barriers were feelings of shame and embarrassment as a result of their situation. This was clearly demonstrated by some of the responses:

“ashamed and embarrassed”

“Very much feeling both ashamed and embarrassed”

These feelings of shame and being embarrassed seemed to be a result of perceptions around normative expectations of IPV and gender. One participant describes being hospitalised and seeing four posters about domestic violence, all of which:

“…were from the female perspective”

There is a clear perception and expectation about IPV being gendered; this can also be seen in the fact the domestic abuse policy falls under the Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy; a strategy where there is no equivalent for men and boys, furthering the view that IPV is gendered. Another participant describes credibility as being a barrier to help seeking as:

“people… simply don’t recognize this kind of abuse.”

These feelings of shame and embarrassment described by the men here supports the existing literature that shows men hold less favourable attitudes towards help seeking and that these attitudes are as a result of men wanting to adhere to masculine gender normative roles and behaviour. Research suggests that male socialisation through things such as sport or male dominated careers (e.g., the army) can implement an indoctrination of masculine expectations which in turn contributes to the construction of male gender identity and behaviour expectations. This acts as a personal barrier because men, as a group, are assumed to have power, and there is a stigma attached to men who do not meet these societal expectations. This can be embarrassing and cause negative attitudes towards help seeking and a reluctance to access it. This may be illustrated by the response from a participant who describes himself as a “6 foot 2 ex squaddie” saying:

“…Moaning about my wife beating me up could turn a friend who admired me into someone who either viewed me as a failure or suspicious that I was really to blame within minutes.”

We found several other personal barriers that stopped men seeking help. For example, trying to keep the family together, false allegations and failure of police and other support organisations to intervene. However, these all in some way or another link to feeling embarrassed, ashamed, or both, as a result of self-stigmatisation from comparing themselves and their situation to what society expects.

Experiences of Control

The men who participated in the study identified a range of methods that were used to control them and how this impacted on their help-seeking. Although we primarily discuss these two themes in isolation, they are closely intertwined; experiences of control may inform a victim’s self-beliefs, and ultimately whether they disclose the abuse and/or seek help. There were recurrent types of control, for example false allegations were threatened or carried out to control the victim, below are quotes extracted from the data:

“I know with certainty that I would have false allegations levelled at me, and this is a major reason why you stay”

Some victims resorted to methods to attempt to challenge any future attempt of false allegation:

“I was threatened with two false allegations (Alcoholism and Threatening with a Knife), I used a digital voice recorder after that and kept diaries. I still keep a diary of events now”

These examples highlight the way false allegations can be used as method of control and why some men remain in a relationship with their abusive partner. The types of false allegations varied from rape/sexual assault to physical violence, this method of control was often more than the threat of police reporting, but seen as a specific area targeted to control them through fear of losing access to their children.

“False allegations were made in order to obstruct contact and access to my child”

Criminality may inflate the perceived risk by services as to whether they will allow parental access, and is also considered in family court proceedings. The use of these tactics to control the men produces a significant barrier to seeking help. Throughout the data it is often stated that there was a fear of not being believed by authorities, which increases the power these methods of control hold against male victims of IPV. Furthermore, if custody of the child was primarily organised in favour of the mother, men spoke of the manipulation of the children to affect their parental relationship (parental alienation). This was used to emotionally abuse (and control) the victim after a separation by continuing the narrative that the victim was to blame for the circumstances which had occurred, which links in with the personal barriers discussed previously. The methods of control discussed are a snapshot of some prolific means women utilised to control their partner, how these impacted them, and ultimately reasons why male victims of IPV may not disclose or seek help.

Taylor, Bates, Colosi and Creer (2019)

Our analysis of this large data set has revealed the myriad of factors that can affect men’s recognition of their need for help and their efficacy in seeking that help. Figure 1 (below) is a thematic map of our analysis and highlights the complexity of barriers that men experience:

Figure 1: Thematic map of barriers to help-seeking

In our upcoming paper, we discuss these barriers in more detail with a specific focus on those related to personal and social identity. We hope our findings can be useful to both academics and practitioners in helping them understand the number of obstacles men face. We further hope, more importantly, that by discussing these barriers beyond academia we may be able to challenge the wider narrative that exists around men’s help-seeking, and could encourage more services and agencies to make changes to reduce some of the political and structural barriers. We hope that men who engage with this work may feel they are not alone and that their experiences and difficulties in disclosing are shared by many others; this may in at least a small way facilitate a reduction in these personal or identity barriers for those men.

The research team:

|

| Attilio |

|

| Andy |

|

| Liz |

|

| Julie |

If anyone has felt upset or distressed by anything they have read here, please note there is support available through these agencies:

Women’s Aid – Domestic Violence Service providing a wide range of services to women experiencing domestic abuse.

0808 2000 247

Mankind Emotional support and practical advice for men experiencing domestic violence.

01823 334244

Galop – Support and advice for people in the LGBTQ+ community who are experiencing domestic violence

0800 999 5428

If anyone would like to find out more about the Student Research Assistant Volunteer Scheme then please email Liz on Elizabeth.Bates@cumbria.ac.uk

Comments

Post a Comment